The legend of Silverheels is an enigma in western history. Although not as widely known as Molly Brown or Baby Doe Tabor, nor founded in nearly as much truth, Silverheels is every bit as romantic and enduring as the frontier land that birthed it. The mysterious character at the story’s center continues to enchant and inspire listeners today, over a hundred years after her supposed life. Though little is known for sure about the woman, her name stands among the likenesses of presidents and pioneers on government buildings and massive scenes of geography all throughout one Colorado region. She has inspired novels, screenplays, and well-received productions of theater. Yet the story of a dance hall girl who sacrificed herself to save a small mining community from a devastating plague remains an elusive saga from Colorado’s past.

During the early days of the Colorado gold rush, there existed a booming mining camp named Buckskin Joe (above), set between the present towns of Fairplay and Alma. In its heyday, Buckskin Joe was a bustling populace of five thousand. The camp sprawled across a lush gulch nestled below the ankles of the Great Divide. Nearby were other such ad hoc civilizations that had recently sprung to life, but Buckskin Joe remained not only the largest, but also the most prosperous of the camps in. In fact, at one time talk circulated of designating it the territorial capitol. It had a reputation of being an extremely “lively” camp. There was no argument that it featured the best entertainment in the region. And as was usually the case in the young west, the camp also showcased steady incidents of violence. Some of Colorado’s first and most bloody acts, including fierce Indian wars and gruesome murder sprees (like those committed by the infamous Felipe Espinosa) took place right in Buckskin’s back yard.

Operating from all directions were stores hawking such necessities as groceries, clothing, and mining supplies. There were two banks, the county courthouse, four hotels, a theater, and a newly constructed post office operated by H.A.W. Tabor himself. And planted randomly on seemingly every other coordinate of the map was Buckskin Joe’s thriving industry of sin. In a town whose population was almost entirely made of single men working long days on cold mountainsides, liquor, gambling, and sex were not only lucrative businesses, but welcomed ones at that.

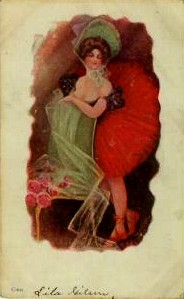

One day, into this harsh settlement of miners and mountain men, a woman no one had ever seen before arrived. She emerged from the Denver Stage, garbed eloquently from head to toe in black. She wore a majestic black dress whose long skirt she gathered in both hands as she descended into the street’s red soil. She was modest in stature, quaint, and inescapably beautiful. Her hair was a deep brunette and bound tightly in a bright silver fillet. Over her face, shadowing her gorgeous features, draped a heavy black veil. This, on top of her striking beauty, kept the mesmerized crowd of onlookers perplexed, inspiring an alluring mystery around the girl.

One day, into this harsh settlement of miners and mountain men, a woman no one had ever seen before arrived. She emerged from the Denver Stage, garbed eloquently from head to toe in black. She wore a majestic black dress whose long skirt she gathered in both hands as she descended into the street’s red soil. She was modest in stature, quaint, and inescapably beautiful. Her hair was a deep brunette and bound tightly in a bright silver fillet. Over her face, shadowing her gorgeous features, draped a heavy black veil. This, on top of her striking beauty, kept the mesmerized crowd of onlookers perplexed, inspiring an alluring mystery around the girl.

She took a job at Bill Buck’s dance hall – a “fancy lady.” The dance hall girls of Buckskin Joe and other raucous mountain encampments of its kind were the ultimate features of entertainment and pleasure – a much-appreciated source of consolation and escape for the miners working in the harsh, unforgiving territory. Moreover, good or bad, being a dance hall girl was the largest, best-paying employment for unmarried women trying to survive in the region. Often flush with a lucky day’s gold strike, miners paid well for a dance with the girls, and even better for a visit upstairs. Buckskin Joe was in no short supply of either commodity as Bill Buck’s place was only one of multiple dance halls in the tiny camp.

Before long she would succeed gold itself as Buckskin Joe’s most prized and sought-after attraction.

It was at Bill Buck’s dance hall that Silverheels got her name. She had secured a job, as well as a small cabin set far off from the town that she is said to have rented from Buck. No one is thought to have ever been invited into the young woman’s cabin. In the time between first arriving in Buckskin Joe and her first night of work, Silverheels kept a low profile. The town was still abuzz about who the beautiful, veiled stranger was and where she had come from. Upon arriving in Buckskin Joe and meeting with Buck, Silverheels went about the town for days, her face hidden behind a heavy veil, thereby creating considerable curiosity.

Then, one evening, among a packed house of gossiping miners, Bill Buck stood atop his bar, fired two crowd-silencing shots into the ceiling, and announced the “unveiling” of his latest dancer.

Then, one evening, among a packed house of gossiping miners, Bill Buck stood atop his bar, fired two crowd-silencing shots into the ceiling, and announced the “unveiling” of his latest dancer.

Upon her entrance, a wave of awestricken silence washed over the room. She removed her hat and veil to a still wide-eyed, hushed mob of spectators. Her dark hair fell heavily around her shoulders. Her features were soft and delicate – defined and lovely, femininely enchanting. She was adorned in a long, tight-fitting wine-colored satin gown. In her hair was tied a bright silver fillet, and, on her feet shined brightly two dazzling silver slippers.

Buck’s audience cheered and applauded in approval, and it is said that it was at this moment, perhaps for no other reason than she never offered a formal title, the girl was given her immortal nickname.

She was a natural. She sang, she danced, she flirted, and, most importantly, she pulled in money. Men proposed marriage on the spot. Silverheels would just smile, place one of her angelic white hands on that of the soil-stained miners, and keep the excitement and the gold flowing.

She became a regular attraction in the camp, and men came from every corner of the region – from the nearby camps of Fairplay, Alma, Montgomery, Mosquito, Hamilton, and Quartsville – to see for themselves this colorful dance hall girl known as Silverheels. While the very few “good” women of the area may have had nothing to do with her, the men (oftentimes even the husbands of such “good” women) would worship the whisky-stained stage her silver heels floated across and would squander what gold they managed to laboriously pull out of the nearby mountains and streambeds for a dance, or a night, with the beautiful Silverheels.

Her new life had only begun when one day there entered into Buckskin Joe two sheepherders, and along with them a disease that would destroy this life.

Smallpox was one of the great terrors of early America. It crept into the colony cities of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City, and later into western camps like Deadwood. Extremely painful, dehabilitating, and disfiguring, smallpox regularly left victims scarred for life, blind, or dead with a 30% mortality rate – a percentage significantly worsened when not properly treated. Exclusive only to humans, it is extremely contagious; passing off between hosts sometimes airborne – simply talking face to face with a carrier was a major risk – or in clothes, bedding, or other cloths and items that make contact with the skin. In 1979 it became the first and still only human infectious disease to be completely eradicated from nature. But in the fall of 1861, the disease was about to devastate the unsuspecting mining town of Buckskin Joe.

The two sheepherders were said to have traveled northeast from Colorado’s San Luis Valley. They stopped in the camp to rest and sell lamb. The mutton was solicited and dispersed all throughout the town to a buying public. But suddenly, not long after first arriving, one of the sheepherders grew extremely and mysteriously ill. By the day’s afternoon he had died. His companion soon came down with the illness, and before the town knew what happened, he too had passed and plague was in the camp.

It started flu-like, then grimly worsened until men were unable to leave their beds, pockmarks meanwhile sprouting all over their bodies.

Citizens fled to Denver and the other nearby towns to sit and wait uneasily for the crisis to end. Suddenly, amidst its booming and rowdy heyday, Buckskin Joe became a ghost town. Signs declaring indefinite closure hung from windows and doors of town businesses like literal signs of Armageddon.

Citizens fled to Denver and the other nearby towns to sit and wait uneasily for the crisis to end. Suddenly, amidst its booming and rowdy heyday, Buckskin Joe became a ghost town. Signs declaring indefinite closure hung from windows and doors of town businesses like literal signs of Armageddon.

Buckskin Joe was in a state of emergency. There are discrepancies in the legend over whether or not anyone ever came to the town’s rescue. According to some, a cry for help was telegraphed to the cities of Denver, Colorado Springs, and Leadville, requesting the immediate deployment of doctors and nurses. Some believe help never was sent, or, if it was, that a major snowstorm stopped them not far outside of South Park and forced them to turn around. Others believe that a few nurses did make it to Buckskin Joe from the cities – as few as two, some say, nurses who were brave enough themselves to risk working through such a dangerously-contagious disease.

It was at this time, amid pain, disease, death, abandonment, tragedy, peril, and heartbreak that Silverheels’ legend would be made. She had stayed, for perhaps no other reason besides to stay with the town – the men – who loved her. She had cast off from wherever it was she came from – perhaps a warm, safe metropolis unscathed by epidemic but beset by something more personally insufferable. Either way, in the desolate and deserted mountain camp of Buckskin Joe she stayed. To the diseased and dying men of the camp, with no wife, family, or friend to care for them, Silverheels was an angel heaven sent. She cared for them, perhaps even like no one in their life previous had ever even so much as showed willing or capable of doing.

She walked in the cold from cabin to cabin administering food, medicine, and, most of all, comfort to the sick. No one was safe; women, children, and men, and it was said that many lives were lost in the epidemic. Many lives were lost but, miraculously, Silverheels, though forlorn and, heartbroken, remained physically healthy. With such a dreadful, scarring disease as the mutilating smallpox, Silverheels, even if she survived a contraction, risked one of her most precious assets: her beauty. Nevertheless, this fear did not seem to ward off the resolute Silverheels as she continued her routine throughout the town of carrying supplies to the cabins and even holding in her arms a coughing and contagious victim.

She walked in the cold from cabin to cabin administering food, medicine, and, most of all, comfort to the sick. No one was safe; women, children, and men, and it was said that many lives were lost in the epidemic. Many lives were lost but, miraculously, Silverheels, though forlorn and, heartbroken, remained physically healthy. With such a dreadful, scarring disease as the mutilating smallpox, Silverheels, even if she survived a contraction, risked one of her most precious assets: her beauty. Nevertheless, this fear did not seem to ward off the resolute Silverheels as she continued her routine throughout the town of carrying supplies to the cabins and even holding in her arms a coughing and contagious victim.

She did this, until finally the spell was broken. It seemed that the epidemic was waning as victims began to recover and those that had evacuated slowly and warily returned. It appeared that Buckskin Joe would live to see another day.

Tragically, it was at this time, in the final hours of the epidemic, that Silverheels would fall.

The final chapter of the Silverheels legend is the most mysterious of them all. It is also the most romantic. For the first time in months there appeared to be hope for the besieged camp of Buckskin Joe. Men still lay achingly in bed, but fewer were falling victim to the epidemic and those that had contracted the illness but were fortunate enough not to have died began to rediscover their health. But one night, in the cabin of one recovering miner – leaning over his bedside as she attended to him – Silverheels collapsed.

The final chapter of the Silverheels legend is the most mysterious of them all. It is also the most romantic. For the first time in months there appeared to be hope for the besieged camp of Buckskin Joe. Men still lay achingly in bed, but fewer were falling victim to the epidemic and those that had contracted the illness but were fortunate enough not to have died began to rediscover their health. But one night, in the cabin of one recovering miner – leaning over his bedside as she attended to him – Silverheels collapsed.

She was carried to her cabin across the river and apart from the huddled town. Once inside, she did not come out. As Buckskin Joe convalesced, Silverheels declined deep into delirium and darkness; the plague seemingly bent on pledging one more victim – she who had braved and defied it – before it was banished forever.

The days passed and the town continued to restore itself. The men and women who had previously fled in fear to wait out the plague returned and reopened their businesses. The stage resumed its normal routes and carried faces new and old into the town. Those who had survived recovered their health and, though scarred, thanked the heavens that they were not one of the many laying in fresh graves in the newly-expanded cemetery. Buckskin Joe was almost back to normal. Almost. Its dance hall queen had still not returned.

According to many versions of the story, only one person in the camp was ever allowed into Silverheels’ cabin, including during the time of the girl’s illness: a grandmotherly and long-time resident called Aunt Martha. According to this popular story, Silverheels had indeed succumbed to smallpox, and as the rest of town had all but resumed normalcy, Silverheels fought a private and painful battle towards recovery. During this time, Silverheels said very little and, even as she got to improve, sat for hours by her single cabin window gazing solemnly at the outside world. One evening during one of Aunt Martha’s visits Silverheels rose to her feet and, offering no explanation, asked the old woman to help her dress. With Aunt Martha’s help Silverheels put on her most elegant dress, tied in her hair her bright silver fillet, and – as if it were the eve of another wild performance on the stage of Bill Buck’s dance hall, slipped her small feet into a dazzling pair of silver-heeled dance slippers.

Then, saying nothing, Silverheels walked to her cabin dresser and from it pulled a small mirror. She lifted the instrument to her face and looked into it deeply. In the dim firelight of the cabin she gazed into the mirror’s glass reflection and studied intently the scars and pockmarks marring her once-beautiful complexion. She stood there for some time. Still: silent and expressionless. Her dry, unblinking eyes betrayed her however. Though they wandered the mirror’s circumference – tracing the deep and permanent blemishes like they were points of a constellation – they hinted at a pain that was not external or bodily, but an ache that cut deep and permanently in her heart.

With that, she put the mirror down and returned to her place near the window. Dressed, but still having announced no occasion, she bid a puzzled and worried Aunt Martha goodnight. It was the last the old woman would ever see of Silverheels.

Meanwhile, the town had grown impatient in awaiting the return of their new heroine, and commenced plans of making some kind of reward for the woman; a token of their extreme gratitude and admiration. A purse was collected for Silverheels by the people of Buckskin Joe. All told, the token of appreciation is said to have amounted to a very impressive $5,000.

But upon reaching her cabin and knocking on its door, the award committee found no one. The door, unlocked, opened to reveal a bed, some clothing, a dresser, and other tells of residency minus the resident. She had vanished.

A search went out for the missing Silverheels. Aunt Martha was questioned but turned up just as confused as the rest of Buckskin Joe. Some feared for the worse, and a lookout was kept for the remains of the girl – if anything surely identifiable by a pair of bright silver dance shoes. But nothing was ever found.

The reward was given back to its donators who accepted it sadly. A heavy sorrow fell on the people of Buckskin Joe. It was an uncomfortable feeling of longing, dissatisfaction, and even a little bit of shame. She had done so much for them, this stranger who had arrived so mysteriously and departed even more so. She had entertained and warmed the hearts of people she did not know. She had comforted the sick and alone when no one else would. She had saved lives. And all the while, throughout it all, she had been sacrificing herself. But she was gone now; gone before anyone even had the chance to thank her.

It was in her honor that the great peak standing over Buckskin Joe and the whole South Park basin was named: Mt. Silverheels. For years the mountain had gone by no real, official name. Some may have called it by its Indian name, Mount-Going-Towards-The-Sun. Others likely called it nothing at all – the mountain remaining an unnamed zenith looming patiently in men’s peripherals, waiting for it’s great significance to be revealed. They could not present Silverheels with a cash reward, or some other tangeable prize. It probably wasn’t befitting to her anyways. The beautiful young woman known fondly as Silverheels could have riches if she had truly wanted them. She had talent, beauty, and a heart that would prosper in any corner of the world. She very well may have even come from such wealth – driven off from that place too by some unforeseen and tragic event. But she had chosen the cold and bleak wild of the mountains and the tiny rambunctious camp of Buckskin Joe as her home. She deserved more than the world gave her, and the least it could do in the end was offer her one of its most beautiful mountains.

It is here that most versions of the Silverheels legend end. A few, however, go on. It is said that in the years following the terrible smallpox epidemic of Buckskin Joe, a mysterious figure would be seen late at night roaming the town’s cemetery. A woman draped in a gray cloak and with a dark veil hanging over her face. Any noise or signal of someone watching sent the cloaked figure running into the cold woods. But some claim to have actually been close enough to see through the veil; to faintly view the pockmarks and scars underneath. Unknowing of any prying eyes, it is said of the woman that she weeps over the graves of the men claimed by the epidemic, those she could not save. She brings flowers and places them upon the tombstones – a symbol that, as in their sickness, so too in death are they loved.

So ends the legend of Silverheels.

Beyond the 13,822-foot Mt. Silverheels, the Silverheels subdivision, Silverheels Middle School, and numerous Silverheels Roads, the presence of this story’s heroine can be found not only in Colorado’s South Park, but on the very brim of pop culture. A painting of the dance hall girl currently hangs in the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. A popular upscale restaurant named and themed in her honor still operates in Colorado’s Summit County. In 1954, Denver University produced an opera based on the legend called Silverheels. Soon after, a play was performed in Central City called … And Perhaps Happiness, which also featured the character and story of Silverheels. Around that time, the story caught the attention of movie star Julie Harris and her producer-husband Manning Gurian. In an interview with The Spectator (date unknown), Gurian declared, “Julie would like to play Silver Heels some day… We promise to read any scripts about Silverheels.” Soon after making the announcement, several scripts were submitted, one of which was considered by MGM, though where the project ended is unknown.

While the story of Silverheels is one mostly rooted in romanticism, its influence on not only the region from where it began but also popular culture is so great as to suggest some true, historical origination. This topic is researched in length, with sources, and published in a 2008 thesis titled Silverheels, A Story of Land, Legend, and Life in 19thCentury Colorado. If you are interested in obtaining a free electronic copy of this work, contact Adam James Jones.